In the late summer of 1830, Dr Thomas Mills of Dublin travelled to Paris with his wife Augusta and sister Kitty. Despite concerns about Thomas’ health, the trio enjoyed a stimulating time meeting friends and seeing the sites of Paris. They stayed at the centrally-located Hôtel des Îsles Britanniques, beside Place Vendôme and Jardin des Tuileries, and the two women experienced the delights of shopping at the vast and glittering Palais Royale. Thomas was more keen to attend political talks and consult with fellow medics. In a letter to his brother back in Dublin,[1] Thomas wrote that he ‘had the good fortune’ to hear General Lafayette, Lafitte and Dupin – all radical, libertarian leaders of the Paris Revolution that had taken place only five weeks earlier.[2]

Who was this Thomas Mills whose ‘heart was pleased’[3] to hear the leading liberal, republican thought-leaders of Paris? There are huge gaps in what we know of the man, and much of the information we have on Mills is drawn from his public profile as a physician. However, we get glimpses of his personal life and private thoughts in a series of letters he wrote from the Armagh and Down countryside, mostly in summer 1805. The letters provide insight into Mills’ personal values and political beliefs as well as presenting acute observations of the lives of people of County Down. The letters are now held in the Royal College of Physicians archive, as part of the Kirkpatrick Collection.[4]

Thomas Mills, Physician ([1773]-1830)

|

| Figure 1 Portrait of Thomas Mills by Martin Cregan 1788-1870, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Ref 1850.3, reproduced under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 |

Radical thinking

At Loughbrickland, Mills came face-to-face

with the realities of the political situation, and its impact on religious

tensions, poverty and local landlord-tenant relations. The village was in the

heart of the countryside and populated by some 600 people,[14]

which he described as being mostly Presbyterian, with some Catholics and

Protestants.[15] This is

important since Mills arrived there soon after the Irish rebellion of 1798, and

the Act of Union (1801), which abolished the Irish parliament and helped build

momentum behind the cause of Catholic Emancipation. Both events created

upheaval and pervaded the thinking of disparate parts of the population.

Although large numbers of Irish people fought with the British against

Napoleon, there was much support for France, particularly amongst those who had

sympathised with the American revolution in the 1780s. This latter group

included certain classes of Catholics, city dwellers and especially, Ulster

Presbyterians.[16] Mills

was amongst this cohort, and his views had been sharpened during his time at

Edinburgh.

Edinburgh at the time was not just a place to

study medicine. Through the 1790s, it was a breeding ground for radical and

novel thinking, and the university was a centre for a specifically Scottish type

of Enlightenment thinking that promoted rationalism, humanism and empiricism.[17]

The ideas of Thomas Paine and his Rights of Man (co-written with

General Lafayette), were widely circulated and discussed, and many new radical

societies emerged that sought political and religious reform. Later in the decade –

just as Mills was graduating – societies of United Scotsmen emerged that

aligned with the United Irishmen.[18] It is highly

likely that Mills was familiar with Irish radical contemporaries like Thomas

Drennan who graduated from Edinburgh medical school twenty-one years before

Mills. In Dublin from the 1790s, Drennan was active in the Volunteer movement and the fight for an independent, reformed Irish

parliament, and was a key leader in the Dublin

Society of United Irishmen.[19]

We know that Mills admired Dr Alexander Crawford of Lisburn, since he called on

him to attend his mother in May 1805.[20]

Dr Crawford was well known and had an extensive medical practice; he was also a

radical and active Volunteer in 1793/4, was implicated in activities with the

French in 1794, and was arrested with other United Irishmen in 1796.[21]

Loughbrickland realities

The young Thomas Mills absorbed these radical, new ideals and they underpinned his perspective and observations on Loughbrickland. With its mix of religions, Loughbrickland was exactly the type of area that experienced repercussions from the 1798 Rebellion, which in many areas led to a decline in interaction and good feeling between Catholics and their neighbours.[22] In July 1805, he wrote ‘religion has a powerful influence on our civil and political opinions’, and observed ‘with regret’ that the longstanding animosity between all classes of Catholics and Protestants had erupted into open disputes. ‘The flame is only smothered’, he wrote, and very little would make the flames ‘blaze forth’.[23] He bewails the ‘depraved’ men who sought to make religion ‘an engine of government’, for the ‘vilest and most base’ reasons.[24] Yet he was not truly a radical, at least in the Edinburgh style: while he sought reform, he believed that religion was fundamental to human development, and could not be easily laid aside.[25]

There are also elements of Lamarckian thinking

in Mills’ letters. Lamarck’s theory posits that a

person’s characteristics could be acquired by behaviour,[26]

and passed through to the next generation. The more radical thinkers, including a number of

medics at Edinburgh University, supported this,[27]

and threads can be seen in Mills’ writing. Mills wrote

that he saw a ‘great number of patients’ with asthma and consumption.

Consistent with his views on fever, he discounts lack of fuel, poor clothing, ‘mode

of living’ and the weather as causes. Rather, he attributes the illnesses

partly to ‘the intemperance and debauchery of our forefathers’, and cites

‘constant inter-marriage of families’ and a ‘long abstinence from animal feed

and other nourishing diet’ as contributing factors.[28]

However,

Mills was not a true Lamarckian, in that he was not an atheist or

anti-Religion; [29] on the

contrary, he frequently mentions the value of religious thinking and

instruction as essential to morality, wisdom and

happiness. He could be seen to be Lamarckian in that he believed that people could,

through their own exertions, advance their position and power.[30]

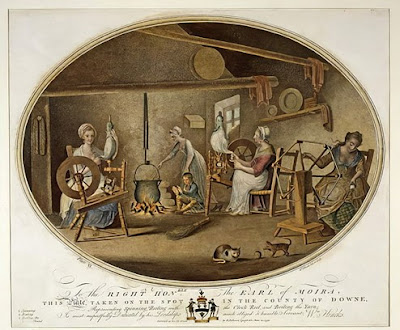

Many of Mills’ letters focus on the work habits and productivity of the people of Tartaraghan and Loughbrickland. He noted the highly-cultivated fields and neat, clean and comfortable looking cabins and he admired the work ethic of farmers who supplemented their farm income by weaving.[31] He also admired the capability and industriousness of women who worked at sewing, spinning, weaving and knitting, and engaged in making hay, digging potatoes, pulling flax and reaping the harvest.[32] He was realistic enough to realise that poor families, no matter how hard they worked, could often not earn enough to ‘provide themselves with the necessities, much less the comforts of life’.[33] Mills’ letters reflect a deep awareness of the unequal distribution of wealth between the land-owning and the tenant classes. He acknowledges that the wealth of people like himself, living ‘in the lap of luxury and pleasure’, depended on the very existence of a discontented tenantry, asking if it should be surprising that ‘such men become rebels’.[34] He even anticipates the potential of a French-style revolution if this is not addressed. He writes, ‘We will not discover, I fear, our real interest, ‘till fatal experience teach it to us - ‘till we taste a little of those sorrows that we have made others feel’.[35]

Overall, Mills' settles on education and

virtue as the best response to poverty and bigotry:[36]

a fairer, more equitable country could be built if young people were taught to

be ‘good citizens’, to ‘admire virtue and despise vice, and to be frugal,

industrious and sober’.[37]

He lauds the local people for sending their children to school,[38]

and conversely, considers the potential for ‘despotism and slavery’ if

property-owners are not well-educated.[39]

He goes so far as to call for a law to prohibit any man ‘unacquainted with the

Principles of Liberty’ from owning Property.[40]

In many ways, Mills appears less a radical and liberal than an Improver,

focusing on relieving poverty and achieving social and moral transformation through economic growth, education, and application of rational,

Enlightenment principals.[41]

Building a career

By September 1805, Mills had gained ‘health

and strength’, and anticipated returning to Dublin.[42]

Unfortunately, we do not know when Mills did settle back in the city. He got

married at a relatively advanced age[43] in 1814 to the 31 year old Augusta Sophia Hamill.[44] Little about the

couple’s personal life is known, except that they lived for a time at the

family home (possibly with Michael Mills) at 41 Dominick Street, Dublin, and by 1829, had moved a street away to 38 Granby Row. As a physician, Mills is recorded as treating patients in Dublin by

the mid-1810s. He is not listed in the 1809 annual report of Cork Street

hospital,[45] though

he may have returned to it in subsequent years, since he wrote a paper in 1813

based on case studies from there.[46]

In one noteworthy intervention, he was called as a witness to the declaration

of a miracle by the Catholic Diocese of Dublin. Mills had been treating Mrs

Mary Stuart, a religious sister in Ranelagh Convent, Dublin in 1823 for four

years prior to her ‘miraculous’ recovery.[47] Mills cannot have

liked the newspaper coverage, and especially the mockery

the

miracle declaration attracted from Protestant clergy

and other physicians. That incident notwithstanding, Mills kept close to the

Dublin medical fraternity and set out to establish his position, with the hope

of rising to the ‘head of my profession’.[48]

Some of the ambition that his brother Michael observed in him at the start of

his career remained,[49]

and Thomas took only a short time to achieve the wealth and ‘higher rank in

society’ that he sought.[50]

Mills published a series of papers and case studies over the years, including essays on blood-letting, typhus, and on various diseases of the liver,

brain and other organs.[51]

By 1824, Mills had consolidated his position as a physician in Dublin. Mills’ ambition saw

him elected as joint vice-President and President of the

Association

of Members of the King and Queen’s College of Physician of Ireland in 1821,[52] and 1823[53]

respectively. While he clearly enjoyed some support from his medical colleagues within the College, Mills never became President or Vice-President of the College itself.

To Paris

Twenty-five years after his letters from

Armagh and Down, Mills travelled to France to alleviate his declining health.[54]

He may have gone to seek a change of air, to recover from overwork and

‘exertion of the intellectual faculties’, or for something more serious.[55]

In his

letter of 3 September 1830, Mills writes that he

consulted with Dr Crawford – ‘a kind friend’ – who advised him to go on

to Nice. He followed the advice, but died there two months

later, on 6 November 1830. He was 57. The

Belfast Newsletter noted the death of this eminent and distinguished

physician who had made an extraordinary contribution to his profession. Mills,

it said, had been an ‘amiable and interesting companion, and a generous

friend’, and his death was ‘a source of deep affliction’ to a wide circle of

friends and colleagues.[56]

After his death, Augusta Sophia continued to reside at their home at 15 Rutland

Square East for at least the next five years;[57] in 1838, she

married Dr William Turner at Malvern Wells in Worcestershire.

Conclusion

While the letters represent a limited source, it seems reasonable to

conclude that Thomas Mills was a radical in his mind, a liberal in his heart,

and a pragmatist in his practice. His observations of country life are acute

and interspersed with the enlightenment ideas and radical principles he honed

at Edinburgh University, but his absorption of these principles and ideals was

selective, particularly in relation to his belief in the value of religion.

That he was sincere in his desire to address the plight of the poor is

evidenced by his taking a position at the Cork Street hospital, and his letters

are infused with sympathy and some empathy for the poor of County Down. He was

not extremist enough to be overtly public with his views; nor did his radical ideals

supersede his position in society or role as a physician, as in the case of

people like Drennan or Crawford. Nor, it turns out, was Mills’ espoused

ambition enough to see him rise to the very top of his profession as he had

wished. The Belfast Newsletter may have been correct in remembering him

as an eminent physician and amiable companion, whose ‘qualifications,

both of head and heart, were of no ordinary description’.[58]

The letters of Dr Thomas Mills are held in the archives of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Heritage Centre, and are part of the Thomas Percy Claude Kirkpatrick Archive, also known as the Dr Kirkpatrick collection.

Fiona Slevin

[1] Thomas

Mills, 3 September 1830, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/26.

[2] The

French Revolution of 1830 took place between 26-29 July 1830, and resulted in

the abdication of Charles X; the king was replaced with a constitutional

monarchy with Louis Philippe on the throne. Lafayette was leader of the

opposition and had been a hero of the American Revolution of the late 1770s; he

co-wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, and was an outspoken advocate of religious

toleration and the abolition of the slave trade. Lafitte was also a member of the Chamber

of Deputies and led the development of finance and banking post-revolution.

Dupin (likely Dupin the Elder), was a magistrate, eminent advocate, and

President of the Chamber of Deputies for eight sessions.

[3]

Thomas Mills, 3 September 1830, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/26.

[4] ‘Letters

from Thomas Mills TPCK/6/3/5, in the Thomas Percy Claude Kirkpatrick Archive’,

n.d., The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Heritage Centre.

[5] Harriet Wheelock,

‘My Dear Mich …’, RCPI Heritage Centre Blog, June 13, 2011; available

from http://rcpilibrary.blogspot.com/2011/06/my-dear-mich.html;

accessed 21 September 2021.

[6]

‘Scottish Enlightenment’, British Council, July 2016; available from https://www.britishcouncil.org/research-policy-insight/insight-articles/scottish-enlightenment;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[7] Laurence

Brockliss, ‘Medicine, Religion and Social Mobility in Eighteenth- and Early

Nineteenth-Century Ireland’, in Ireland and Medicine in the Seventeenth and

Eighteenth Centuries, eds. James Kelly and Fiona Clark (London, 2016), p

77.

[8] Harriet Wheelock,

‘My Dear Mich …’, RCPI Heritage Centre Blog, June 13, 2011; available

from http://rcpilibrary.blogspot.com/2011/06/my-dear-mich.html;

accessed 21 September 2021.

[9] ‘Cork

Street Fever Hospital and House of Recovery’, Cork Street Fever Hospital,

October 2015; available from http://corkstreetfeverhospital.ie/;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[10]

Thomas Mills, 1 May 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/2.

[11]

Thomas Mills, 1 May 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/2.

[12] John

Farmer, Patients, Potions & Physicians: A Social History of Medicine in

Ireland, 1654-2004, (Dublin, 2004), p71, 74.

[13]

Thomas Mills, 18 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/8.

[14]

Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, (Dublin, 1837),

lists the population as 617 people.

[15]

Thomas Mills, (n.d. possibly 1 or 2) July 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/5.

[16] Kennedy,

W. Benjamin, Catholics in Ireland and the French Revolution, Records of

the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Vol 85, No.

3/4, 1974, pp 221.

[17]

‘Scottish Enlightenment’, British Council, July 2016; available from https://www.britishcouncil.org/research-policy-insight/insight-articles/scottish-enlightenment;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[18]

‘Scotland and the French Revolution’, The Scottish History Society,

n.d.; available from https://scottishhistorysociety.com/scotland-and-the-french-revolution/;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[19] A.T.Q.

Stewart, ‘William Drennan’, in Dictionary of Irish Bibliography,

October 2009, Royal Irish Academy, https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.002765.v1, accessed 9 December

2021.

[20] Thomas

Mills, 14 May 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/4.

[21] C.J.

Woods, ‘Alexander Crawford’ in Dictionary of Irish Bibliography,

revised December 2010, Royal Irish Academy, https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.002156.v2, accessed 9 December 2021.

[22]

John Gamble, edited by Breandán Mac Suibhne, Society and manners in early

nineteenth-century Ireland, Field Day, 2011, XXV.

[23] Thomas

Mills, 12 July 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/10.

[24]

Thomas Mills, 12 July 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/10.

[25]

Thomas Mills, 1 September 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/17.

[26] P.J.

Bowler, ‘Evolution, History Of’, in International Encyclopedia of the Social

& Behavioral Sciences, ed. Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (Oxford,

2001), 4986–92; available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0080430767030679.

[27]

Adrian Desmond, The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in

Radical London (Chicago, 1989), 5.

[28]

Thomas Mills, 29 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, RCPI Kirkpatrick

Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/15.

[29]

Adrian Desmond, The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in

Radical London (Chicago, 1989), 4.

[30]

Adrian Desmond, The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in

Radical London (Chicago, 1989), 5.

[31]

Thomas Mills, 9 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/1.

[32]

Thomas Mills, 28 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, RCPI Kirkpatrick

Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/13.

[33] Thomas

Mills, 30 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/16

[34]

Thomas Mills, 3 July 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/5.

[35] Thomas

Mills, 3 July 1805, p9- 10, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/5.

[36]

Thomas Mills, 13 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/4.

[37]

Thomas Mills, 13-14 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/5.

[38]

Thomas Mills, (n.d., possibly 1 or 2 July 1805), RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive,

TPCK/6/3/5/5.

[39]

Thomas Mills, 18 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/9.

[40]

Thomas Mills, 18 August 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/9.

[41] W.

Forsythe, ‘The Measures and Materiality of Improvement in Ireland’, International

Journal of Historical Archaeology 17, no. 1 (2013), 73.

[42]

Thomas Mills, 4 September 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/19.

[43] Maria

Luddy and Mary O’Dowd, eds., ‘Meeting and Matching with a Partner’, in Marriage

in Ireland, 1660–1925 (Cambridge, 2020), 91–134; available from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/marriage-in-ireland-16601925/meeting-and-matching-with-a-partner/EDDDE9E6E154ED7B3DAF063F99B75B9E;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[44] Probate

Record and Marriage License Index, 1270-1858, Keeper of the Public Records

in Ireland, (Dublin, Ireland), 745; available from www.ancestry.co.uk;

accessed 24 November 2021.

[45] Annual

Report of the Managing Committee of the House of Recovery, and Fever-Hospital,

in Cork Street Dublin, for the Year Ending 4th January, 1809 (Dublin,

1809); available from http://corkstreetfeverhospital.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1808.pdf;

accessed 9 December 2021.

[46]

An essay on the utility of Blood-Letting in Fever, (Dublin, 1813).

[47] Belfast

Newsletter, 22 & 29 August 1823; The Freeman’s Journal, 25

August 1823.

[48]

Thomas Mills, 1 May 1805, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/2.

[49]

Michael Mills, 13 May 1824, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/21.

[50]

Michael Mills, 13 May 1824, RCPI Kirkpatrick Archive, TPCK/6/3/5/21.

[51] An

essay on the utility of Blood-Letting in Fever, (Dublin, 1813); The

Morbid Anatomy of the Brain in Typhus Fever, (Dublin, 1817); Observations

on the Diseases of the Liver’ (Dublin, 1811 and 2nd edition

1821); An Account of the Morbid Appearances exhibited on Dissection in

various Disorders of the Brain, (Dublin, 1826); and An Account of the

Morbid Appearances exhibited on Dissection in Disorders of the Trachea, Lungs

and Heart, (Dublin, 1829).

[52]

The Freeman’s Journal, 11 May 1821.

[53] Transactions

of the Association of Fellows and Licentiates of the King’s and Queen’s College

of Physicians in Ireland. Volume 4, 1824, digitised by Wellcome

Library; available from http://archive.org/details/s3id13658270;

accessed 25 November 2021.

[54] Belfast

Newsletter, 26 Nov 1830..

[55] Richard

E. Morris, ‘The Victorian “Change of Air” as Medical and Social Construction’, Journal

of Tourism History 10, no. 1 (January 2, 2018), 4.

[56] Belfast

Newsletter, 26 Nov 1830.

[57] Pettigrew and Oulton, The Dublin Almanac and General Register Of Ireland,

1835, 308.

[58] Belfast

Newsletter, 26 Nov 1830.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.